Documentary research on languages

My research is grounded in long-term, corpus-based documentary work on underdescribed and endangered languages. I work primarily on two language groups: Western Tibetic languages of Ladakh (India) and Eastern Hindi (Indo-Aryan) languages of north-central India. Across both areas, my work combines field-based documentation, phonetic and morphosyntactic analysis, archiving, and community-oriented engagement.

Western Tibetic languages

My primary research focus is on Zangskari, a Western Tibetic language spoken in the Zangskar Valley of Ladakh, India. Since 2020, I have conducted sustained fieldwork on Zangskari, resulting in a growing audiovisual corpus spanning multiple genres, including personal narratives, historical narratives, interviews, and verbal art (notably the Zangskari version of the Epic of Gesar). My work aims to contribute both to linguistic theory and to long-term documentation and revitalization efforts.

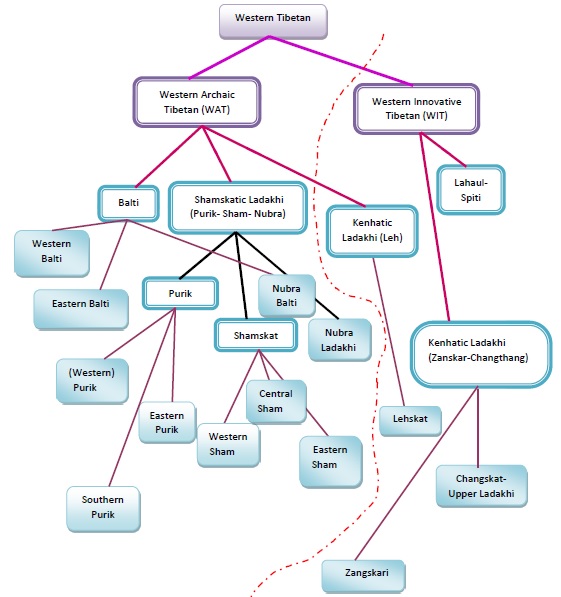

Western Tibetic varieties are often discussed in terms of phonological conservatism versus innovation, particularly with respect to the retention or loss of Old/Classical Tibetan consonant clusters. Following phonetic criteria, Zeisler (2011:235) proposes a broad distinction between:

- Western Archaic Tibetan (WAT) varieties, which retain initial consonant clusters and syllable-final consonants and are typically non-tonal (e.g. Balti, Purik, Sham, Nubra, Leh), and

- Western Innovative Tibetan (WIT) varieties, in which clusters have been reduced or lost, often accompanied by compensatory tonogenesis (e.g. Upper Indus, Changthang, Zangskar).

At the same time, purely phonetic classifications do not capture important morphosyntactic divisions. On morphosyntactic grounds, Zeisler (2011, 2018) distinguishes between two broader groupings within Ladakh:

- Shamskatic varieties, spoken primarily in north-western Ladakh (Purik, Sham, Nubra), and

- Kenhatic varieties, spoken in south-eastern Ladakh (Leh, Upper Indus, Changthang, Gya–Miru, and Zangskar).

One salient difference between these groups is the treatment of agent and possessor marking: Kenhatic varieties do not formally distinguish between these roles, whereas Shamskatic varieties do (Zeisler 2018:78). In this framework, Zangskari patterns morphosyntactically with the Upper Indus and other Kenhatic varieties, despite its phonological innovations.

My work on Zangskari engages directly with these classification issues by providing detailed phonetic, phonological, and morphosyntactic evidence from a documentary corpus, contributing to a more empirically grounded understanding of variation and subgrouping within Western Tibetic.

Classification of Western Tibetic varieties:

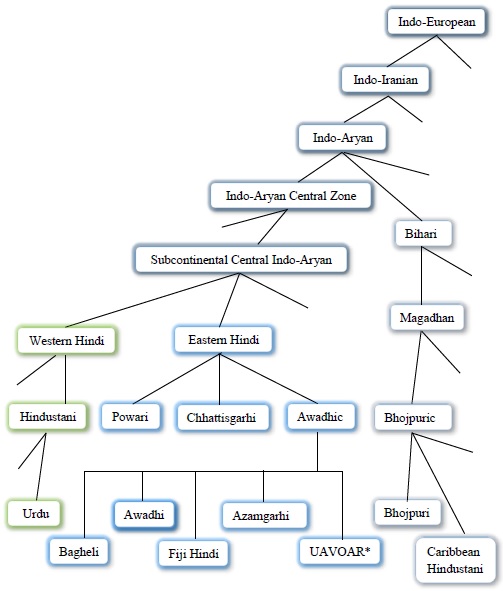

Eastern Hindi languages

Alongside my work on Western Tibetic, I have carried out documentary and descriptive research on Eastern Hindi (Indo-Aryan) languages, with a particular focus on Azamgarhi, my heritage language.

Eastern Hindi is commonly divided into Chhattisgarhi, Powari, and Awadhic subgroups. The Awadhic subgroup itself comprises several regional varieties, including Awadhi, Bagheli, Fiji Hindi, and a range of lesser-described or undocumented Awadhic varieties spoken outside the historical Awadh region.

My M.Phil. research focused on verb morphology in Azamgarhi, an underdescribed Awadhic variety spoken in eastern Uttar Pradesh. Through fieldwork and corpus development, my work documents morphosyntactic patterns that both align with and diverge from better-described Awadhic varieties, highlighting the internal diversity of Eastern Hindi and the need for fine-grained documentation beyond standard language labels.

In addition to Azamgarhi, I have worked comparatively on Western Bhojpuri of the greater Azamgarh region, particularly in relation to language contact, sociolinguistic influence, and structural variation in the Eastern Hindi–Bihari transition zone.

Classification of Eastern Hindi varieties (with Bhojpuri and Urdu shown for comparison):